|

Colonial Kabale

This legend is important in terms of the history of the area as a British officer in Kigezi had concluded in a letter to the Chief Secretary for Uganda on 6th September 1911 that the Nyabingi cult was "entirely subversive to all authority, whether local or European". As such, meaningful attempts to impose colonial rule initially proved fruitless. By the 1930s, missionaries were abundant in the area, having first been visited by the Catholic missionary, Yowana Kitagana in 1911, spreading Christianity. However, there were ongoing superstitions that some of those who were converted to Christianity were later possessed by the spirit of Nyabingi, fermenting a low-level but nonetheless very real simmering of discontent with the British. In 1932, Kabale became a township with an administration invested in a township authority overseen by the Protectorate Governor. | |

To provide some semblance of authority, the British then decided to appoint agents from the Buganda Kingdom to govern the area on their behalf and named their first Kiga chief in Kigezi or Secretary General of Kigezi as Paul Ngorogoza in 1946. Although Ngorogoza did not know English, he was helped by using Kiswahili, which he had picked from Baziba clerks, and the support from Saza and Gomborora Chiefs.

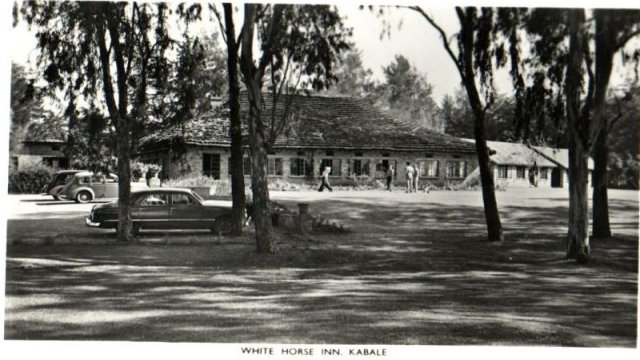

The colonial period brought about significant changes to the socio-economic and political landscape of Kabale. Infrastructure, though primarily serving colonial interests, began to develop with the construction of roads, administrative buildings, schools established by Christian missionaries, and rudimentary health centres. The introduction of cash crops like coffee, tea, and later pyrethrum, integrated Kabale into the global market economy, shifting traditional subsistence farming patterns. However, these changes often came at a cost, including forced labour (effectively corvée labour for public works), and the imposition of taxes that compelled people to engage in wage labour or cultivate cash crops to earn money. The colonial period brought about significant changes to the socio-economic and political landscape of Kabale. Infrastructure, though primarily serving colonial interests, began to develop with the construction of roads, administrative buildings, schools established by Christian missionaries, and rudimentary health centres. The introduction of cash crops like coffee, tea, and later pyrethrum, integrated Kabale into the global market economy, shifting traditional subsistence farming patterns. However, these changes often came at a cost, including forced labour (effectively corvée labour for public works), and the imposition of taxes that compelled people to engage in wage labour or cultivate cash crops to earn money.

The Christian missionaries, alongside the quasi-colonial administration, continued to exert a powerful influence, introducing new religions and Western education, which gradually began to erode traditional spiritual beliefs and practices, and fostered the emergence of a new educated elite. The demarcation of international borders also profoundly impacted the pre-existing fluid movements and relationships between communities, separating kin and disrupting established trade routes. Yet, despite these profound impositions, the people of Kabale, and particularly the Bakiga, demonstrated remarkable resilience, adapting to new realities while striving to preserve their cultural heritage.

|

The colonial period brought about significant changes to the socio-economic and political landscape of Kabale. Infrastructure, though primarily serving colonial interests, began to develop with the construction of roads, administrative buildings, schools established by Christian missionaries, and rudimentary health centres. The introduction of cash crops like coffee, tea, and later pyrethrum, integrated Kabale into the global market economy, shifting traditional subsistence farming patterns. However, these changes often came at a cost, including forced labour (effectively corvée labour for public works), and the imposition of taxes that compelled people to engage in wage labour or cultivate cash crops to earn money.

The colonial period brought about significant changes to the socio-economic and political landscape of Kabale. Infrastructure, though primarily serving colonial interests, began to develop with the construction of roads, administrative buildings, schools established by Christian missionaries, and rudimentary health centres. The introduction of cash crops like coffee, tea, and later pyrethrum, integrated Kabale into the global market economy, shifting traditional subsistence farming patterns. However, these changes often came at a cost, including forced labour (effectively corvée labour for public works), and the imposition of taxes that compelled people to engage in wage labour or cultivate cash crops to earn money.